Teaching guide: financial markets and monetary policy

This resource is provided to assist you in delivering the ‘Financial markets and monetary policy’, which is section 4.2.4 of the A-level specification. Some of the content was included in the previous specification; this guide will focus primarily on those areas which are new or have changed.

The ‘Financial sector’ is included as an area of study in the national ‘GCSE Subject Level Conditions and Requirements for Economics’ and all specifications are expected to cover the following:

- The role of the financial sector and its impact on the real economy

- Financial regulation

- Role of central banks

A-level Economics specifications are also required to cover the nature and impact of monetary policy.

For many years, the nature and role of the financial sector has been a neglected area of study in many Economics courses. The global financial crisis of 2007– 08 and its aftermath have served to emphasise the importance of this sector of the economy for the prosperity of us all.

During their course of study, students will be expected to develop an appreciation of the vital role that is played by financial markets in a modern economy; this includes their importance in allocating scarce resources. They should understand the consequences for the real economy when financial markets do not function well. As Keynes said: ‘When the capital development of a country becomes a by-product of the activities of a casino, the job is likely to be ill-done.’ (The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, 1936).

Students should also understand reasons why financial markets are susceptible to periodic crises and be able to assess some of the measures that the authorities might take to regulate and control such markets. In addition, students should appreciate the role of monetary policy in managing the economy. They should understand how monetary policy is implemented in the UK and be able to evaluate the strengths and limitations of monetary policy measures.

This part of the AQA specification links very closely with a number of other areas of the specification, for example, the sections on ‘Economic growth and the economic cycle’ and ‘Economic growth and development’. The efficiency and effectiveness of financial markets will influence both the short-run and long-run growth of developed economies. In developing economies, the inadequacies of the financial infrastructure can act as a significant barrier to growth. Instability in financial markets is a major cause of fluctuations in economic activity.

There are also links with aspects of behavioural economic theory. Students should appreciate that the behaviour of individuals operating in financial markets may not always be entirely rational and that this can lead to speculative bubbles and financial instability, for example. Another quote attributed to Keynes, ‘The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.’ illustrates that many economists have long recognised that instability can persist in financial markets and cause serious problems for both individual economies and the global economy.

Overview

This overview provides a summary of the content of the ‘Financial markets and monetary policy’ section of the specification. Further detail is provided later. The guide provides a comprehensive coverage of the new topics, indicating the depth of knowledge required. It does not, however, provide full coverage of the topics that were also included in the previous specification.

The structure of financial markets and financial assets

Students are expected to develop an appreciation of the role that financial markets perform in the wider economy and to recognise that there are various sub markets that comprise the financial sector of an economy. In particular, they should understand the difference between the money market, the capital market and the foreign exchange market. They should also be aware that there are other financial markets such as the markets for commodity futures and insurance products. Students should understand the nature and functions of money, recognising the importance of money in a modern economy. The difference between debt and equity should be understood and how this relates to the financing of business and governments. In addition, they should be able to calculate the yield on financial assets and to explain why there is an inverse relationship between interest rates and bond prices.

Commercial banks and investment banks

It is expected that students should understand the difference between a commercial bank and an investment bank but should recognise that many banks are engaged in both commercial and investment banking activities. They should understand that commercial banks raise the funds by accepting deposits and make profits by lending to individuals, firms and governments. They should know that banks can also raise substantial amounts of money by borrowing in wholesale markets, eg by issuing bonds. Their role in facilitating payments for goods and services should be appreciated. Students should recognise that, unlike commercial banks, investment banks do not take in deposits from customers. Their activities include: helping firms to issue shares and raise finance, assisting with mergers and acquisitions, investment management and trading securities and foreign exchange.

The risks that banks incur through borrowing short term and lending long term should be understood and the way in which banks attempt to manage this risk should be illustrated by looking at the general structure of a typical commercial bank’s balance sheet. The balance sheet can also be used to illustrate how banks attempt to reconcile the potential conflicts between liquidity, profitability and security. Students should also understand that banks create deposits by providing loans. They should recognise that bank deposits are the main component of the money supply and appreciate some of the factors that limit the banks’ ability to create deposits such as their capital reserves, their holdings of liquid assets and the demand for loans.

Central banks and monetary policy

Much of this part of the specification was included in the previous specification although, since that was written, new monetary policy instruments have been introduced and will continue to evolve. It should be understood that a central bank has two main responsibilities, ie to support the government in maintaining macroeconomic stability and to maintain financial stability. Central banks use monetary policy to try to achieve macroeconomic stability and students are expected to keep up to date with any significant changes in the way in which monetary policy is implemented in the UK. They should also recognise the importance of the lender-of-last-resort function in achieving financial stability.

The regulation of the financial system

The financial crisis in 2008–09 has highlighted the problems that can develop in financial markets and financial institutions, and how these problems can seriously impair the performance of the real economy. In the UK, the government has responded by changing how individual financial institutions and the financial sector as a whole is monitored and regulated. Students should understand the role of the Bank of England in maintaining the stability of financial institutions and markets through its use of the lender-of-last-resort function, the work of the Bank’s Financial Policy Committee (FPC) and Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA). They should also have a general awareness of the role of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). It should be understood that bank failures can result from a critical shortage of liquidity and from insufficient capital. Whilst students will not be expected to calculate liquidity and capital ratios, they should understand their importance when assessing the stability of banks.

Resources

A selection of texts and online resources are included to support your teaching.

The structure of financial markets and financial assets

a) Financial markets

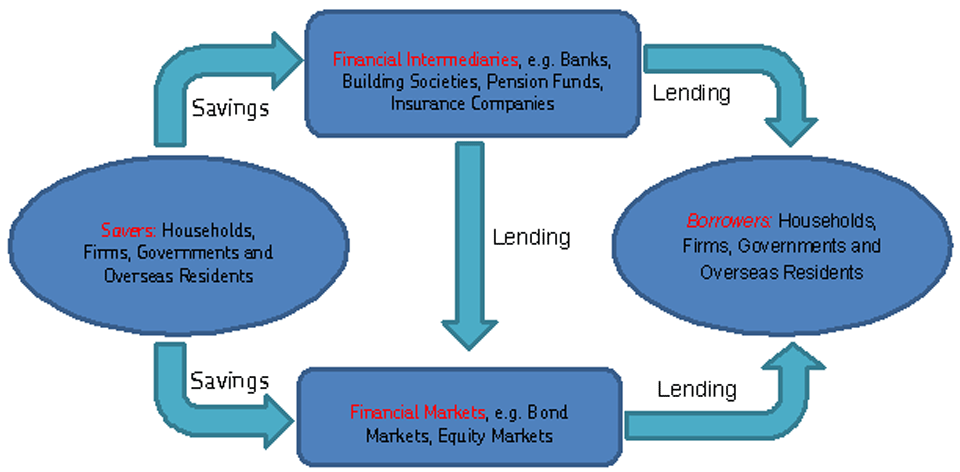

The fundamental purpose of financial markets is to channel funds from those who have surplus funds, those who wish to spend less than their income, to those who have a shortage of funds, those who wish to spend more than their income. For example, people may wish to save through a pension fund for their retirement whilst firms may wish to borrow funds to finance the expansion of their business. This process of channeling funds can take place through a financial intermediary, such as a bank, or may take place directly through financial markets, eg when a company issues new shares or the Debt Management Office of the Treasury issues government bonds

In today’s global economy, there are massive financial flows between economies and this is reflected in the chart above. For example, the Norwegian government might invest some of its sovereign wealth fund into UK government bonds, or a UK pension fund might invest in shares on the Tokyo stock exchange.

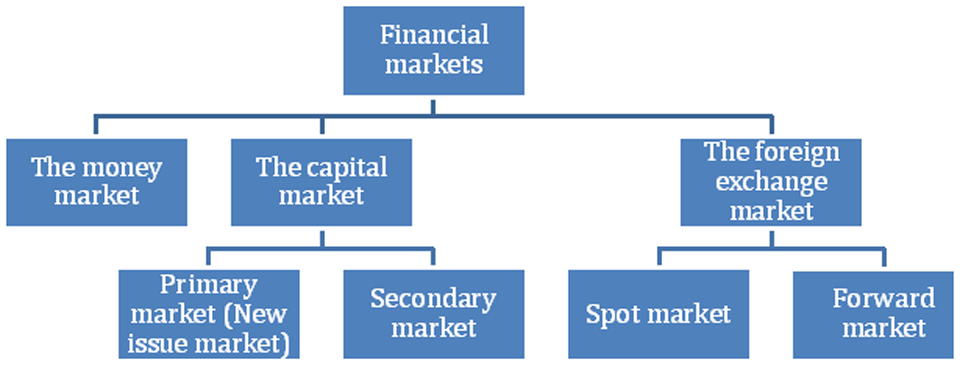

Whilst it is desirable that students are aware that there is a wide variety of financial markets, they are only required to know the difference between the money market, the capital market and the foreign exchange market.

The money market

The money market is a financial market which provides short-term finance to individuals, firms (including banks and other financial institutions) and governments. Short-term debt may have a maturity ranging from 24 hours to perhaps 12 months, interbank lending and lending to the UK government through the purchase of Treasury bills are money market transactions

The capital market

The capital market provides medium and long-term finance to firms and governments. Companies may raise long-term finance by issuing shares or corporate bonds but they can also, for example, borrow from the banks. Governments issue bonds to finance their borrowing needs. The banks also raise money on capital markets to support their lending by issuing bonds. The capital market can be divided into the primary market, or new issue market, and the secondary market. The primary market is where newly issued securities are sold by companies and governments. Secondary markets trade previously issued or second-hand securities; the world’s stock exchanges are important institutions in secondary markets. The principal function of a secondary market is to increase the liquidity of second-hand securities, making it easier for buyers to manage their investments and sell their securities when required. This in turn makes it more likely that those with surplus funds will be willing to buy new issues of shares and bonds.

The foreign exchange market

The foreign exchange market is the market in which different currencies are bought and sold. International trade and international investment flows mean that economic agents will need to convert the funds they provide or receive from one currency to another, eg the pound sterling into euros or dollars. Foreign exchange can be traded on either the spot market or the forward market. Spot transactions involve the immediate exchange of foreign currency whereas forward markets involve the exchange of foreign currencies at some specified time in the future. Forward markets are used by, for example, exporters and importers to protect themselves against exchange rate risks. Foreign exchange markets are frequently subject to bouts of speculation.

b) Debt and equity capital

Students should understand the key differences between debt and equity. They should recognise that bonds are an example of debt capital and shares are an example of equity capital. Debt involves borrowing money that has to be paid back with interest whereas equity involves giving the provider of funds an ownership stake in the enterprise and a share of future profits. The interest on debt is a fixed cost for the business which has to be paid before profits are calculated and any dividends are paid to shareholders. Debt also includes the funds that firms borrow directly from banks and other financial institutions such as loans and overdrafts.

Both governments and large corporations issue bonds to raise finance. Governments issue bonds to finance the budget deficit, ie governments borrow when they are spending more than they receive from taxation. The value of government bonds outstanding at a point in time represents the majority of the national debt, ie the stock of government debt accumulated over the generations. UK government bonds are owned by both domestic and overseas residents. Corporate bonds are issued to finance investment and the expansion of the business. Many bonds pay a fixed rate of interest known as the coupon. The coupon is expressed as a percentage of the nominal value of the bond. Bonds are a form of marketable loan, ie they can be bought and sold in the secondary bond markets. The issuer of the bond is the debtor and the holder of the bond is the creditor. Bonds usually have a fixed maturity date, which is when the issuer of the bond, eg the government, will repay the bondholder the money borrowed.

c) Bond prices, market interest rates and yields

The yield on a bond is the annual interest payment, or coupon, expressed as a percentage of the market price of the bond. Assuming the coupon is a fixed annual amount, if the market price of the bond falls the yield will increase and if the price of the bond rises the yield will fall.

Example 1: Calculating the yield

A bond is issued with a nominal value of £100 and the annual coupon is £4. The bond has 40 years until it matures. Two years after the bond was issued, the market price of the bond falls to £80. Calculate the current yield on this bond.

Understanding why there is an inverse relationship between bond prices and market interest rates is a key element in understanding some of the channels through which Quantitative Easing (QE) can affect the real economy. A simple numerical example can help to illustrate this relationship.

Example 2: Illustrating the inverse relationship between market interest rates and bond prices

A bond is issued with a nominal value of £100 and the annual coupon is £6. When the bond was issued, it offered a return that was similar to other comparable securities, ie the market rate of interest was around 6%. Four years later, the market rate of interest has fallen to 3%. This bond will not mature for many years yet. Calculate the approximate market price of this bond.

The key to this calculation is to recognise that markets will ensure that the yields on securities that have identical degrees of risk will be very similar. In this case, the yield on the bond will fall to around 3% so that it matches the rate of return (yield) earned on other similar assets.

If the current market price was less than £200, investors would clamour to buy this bond since it would offer a higher rate of return than can be achieved on similar securities; the increase in demand would push up the price. If the current market price was more than £200, investors would not be willing to buy this bond since it would provide a lower rate of return than could be achieved on similar securities; bond holders would have to accept a lower price if they wished to sell their bonds.

Since the overall return on bonds depends on possible capital gains as well as current yields, in practice, fluctuations in bond prices are unlikely to be as large as suggested by this simple example. The time until maturity and expectations of future movements in interest rates, and hence bond prices, will affect the likelihood of capital gains and losses.

Students should be able to calculate the yield on securities and use a simple numerical example to illustrate why there is an inverse relationship between market interest rates and bond prices. They will not, however, be expected to take into account possible capital gains or losses. Nevertheless, teachers might wish to explore this issue to challenge the more able students.

d) Functions of money and the money supply

This topic is covered by most existing A-level textbooks. Students should recognise that money is an asset that can be used as a medium of exchange. They should understand the following functions of money:

- medium of exchange

- store of value

- measure of value

- standard of deferred payment

The last two functions in the list above are sometimes combined and called the ‘unit of account’ function.

Students should also be able to distinguish between the functions of money and the essential characteristics of money, such as money should be: portable, divisible, durable, limited in supply, acceptable and difficult to forge.

They should understand the role that money plays in a modern economy recognising that without the development of money, the improvements in living standards that have taken place, for example through specialisation, would not have been possible.

Whilst it is not essential that students have detailed knowledge of any particular definition of the money supply they do need to understand that deciding which assets should be included in a definition of the money supply is not easy. They should understand that the money supply is the existing stock of assets that are classified as money. They should be aware that there are narrow definitions of the money supply and broader definitions that include a wider range of assets,some of which may not be immediately available to use as a medium of exchange.

Students should recognise that a key reason why economists are interested in what is happening to the stock of money is because some economists believe that there is strong relationship between the growth in the money supply and the growth in nominal aggregate demand. However, the stability of this relationship is disputed. Also, there is disagreement over the extent to which changes in the stock of money lead to changes in aggregate demand or whether changes in aggregate demand drive changes in the stock of money. This links closely with section 4.2.3.3 of the specification that includes ‘Fisher’s equation of exchange MV = PQ and the Quantity Theory of Money in relation to the monetarist model’.

Commercial banks and investment banks

a) Commercial banks

Students should recognise that the commercial banks are the ‘high street banks’ and that they have three primary functions: accepting deposits, lending to economic agents and providing efficient means of payment. They should also be aware that, in addition, they fulfil a number of subsidiary functions such as providing foreign exchange and a variety of other financial services to customers. As a financial intermediary, commercial banks play a key role in channelling funds from economic agents who have surplus funds (lenders/savers) to those who can make use of those funds (borrowers). However, it should also be understood that when a bank gives a loan to a customer it creates an equivalent deposit, increasing the money supply. Banks do not just simply lend out money that has been deposited with them, they can also create money.

As private sector organisations, commercial banks are in business to make profits for their shareholders but they also need to be sufficiently liquid to meet the legitimate demands of their depositors. Failure to do so will lead to a run on the bank and the likely collapse of the business. However, there is a conflict between the aims of profitability and liquidity since, generally, liquid assets yield a lower rate of return than those which are more illiquid. The trade-off between security and profitability should also be understood, for example, secured loans, such as mortgages, are likely to be less profitable than unsecured loans. To some extent, the way in which banks manage risk and the trade-offs between the objective of profitability and the objectives of liquidity and security can be seen by looking at a typical commercial bank’s balance sheet.

On a balance sheet, total assets must equal total liabilities. Assets are the claims that a bank has against others and represent how the bank has used its funds. Liabilities are the claims that other people have on the bank and they show the source of the bank’s funds. Liabilities can be subdivided into ‘shareholders’ funds’ and money that the bank has borrowed from depositors or, for example, by issuing bonds. Shareholders’ funds are the bank’s capital and comprise the money that was received when shares were issued plus any retained profits. The following is a general representation of a typical commercial bank’s balance sheet:

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

|---|---|

|

Cash (notes and coins) |

Share capital |

|

Balances at the Bank of England (All settlement banks and some others have an account at the Bank of England. Many of the smaller banks have an account with a different, large bank.) |

Reserves (retained profits) |

|

Money at call and short notice (eg money borrowed from other banks via the interbank market) |

Long-term borrowing (eg bonds issued by the bank) |

|

Bills (commercial and Treasury bills) |

Short-term borrowing from money markets |

|

Investments (eg holdings of government and corporate bonds) |

Deposits (sight deposits and time deposits) |

|

Advances (eg loans and mortgages made to the customers of the bank) |

|

|

Fixed assets (eg premises) |

Note: The capital of the bank (the shareholders’ funds) comprises issued share capital plus reserves.

The first four items on the asset side of the balance sheet are fairly liquid whereas investments and advances are less liquid but are generally much more profitable. Students should understand that banks have to manage their portfolio of assets to ensure that they can meet their customers’ demands for cash whilst also aiming to make a profit for their shareholders. They should also appreciate that banks generally borrow short term and lend long term. This puts them at risk because depositors, for example, may decide to withdraw their money but the bank cannot insist that the people to whom they have lent money, eg mortgage holders, repay immediately.

The most profitable of the banks’ assets are often the most risky. If a bank invests in assets which fall in value, eg because some customers default on their loans, this will result in losses and reduce the banks’ capital. If the reduction in the value of a bank’s assets is so large that it wipes out the whole of the bank’s capital, the bank is technically bankrupt and cannot continue trading.

|

Assets |

£bn |

Liabilities |

£bn |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Liquid Assets |

50 |

Capital |

20 |

|

Investments |

40 |

Long-term borrowing |

10 |

|

Advances |

110 |

Deposits |

170 |

|

Total Assets |

200 |

Total liabilities |

200 |

In the example above, if the value of the bank’s assets falls by more than £20bn, its capital will be wiped out and it will be bankrupt.

Lending long term and borrowing short term means that banks are inherently unstable and a key role of a central bank is to maintain the stability of financial markets. One of the main ways in which they fulfil this function is by providing ‘liquidity insurance’, ie they act as ‘lender of last resort’ to the banks. However, this does not mean that the central bank will bail out a bank that has made bad investments and is making losses. Generally, the central bank will only act as lender of last resort to banks that are fundamentally sound but suffering from a temporary shortage of liquidity.

In summary, there are two fundamental reasons why a bank may fail:

- it suffers a fall in the value of its assets that is so large that its capital is wiped out, ie it becomes insolvent;

- it does not have sufficient liquidity to meet the legitimate demands of its depositors.

In many cases, banks fail when the value of their assets is falling and it is feared that they may become insolvent. In these circumstances, people and other institutions withdraw funds from the bank, ie there is a run on the bank. The bank usually fails because it runs out of liquidity before it becomes technically insolvent.

b) Investment banks

Nowadays, many banks carry out both commercial and investment banking activities but in response to the financial crisis, the authorities are introducing regulations designed to separate these activities. Following The Vickers Report, commercial banking (or retail banking) activities of the banks are to be ring fenced from their investment banking activities. Under current plans, ring fencing must be in place by 2019.

Students should have a basic knowledge of the types of activities in which investment banks are engaged. A key function of investment banks is to help companies raise finance by, for example, giving advice and helping to arrange new issues of shares and corporate bonds. A government that wishes to privatise a public sector enterprise is likely to employ an investment bank to help them. Firms planning a merger or a takeover will also turn to investment banks for advice regarding price, timing and tactics. The investment bank will charge a fee for providing these services. Investment banks are also involved in the secondary market; they buy and sell securities on behalf of clients but also on their own behalf. Buying and selling securities on their own behalf is known as ‘proprietary trading’ and is a risky activity. Other risky activities in which some investment banks are involved include commodity trading and dealing in foreign exchange. Investment banks are often market makers; they enable economic agents to buy and sell securities without using formal exchanges.

The growing tendency for banks to carry out both commercial and investment banking activities is believed by some to have contributed to the recent financial crisis but it wasn’t only the ‘universal banks’ who failed, eg Northern Rock was a commercial bank. ‘The Vickers Report’ recommended that the core functions of the retail or commercial banks should be ring fenced so that if a bank is failing, the situation is easier to manage and retail deposits can’t be used to subsidise ‘casino’ banking. This approach is an alternative to forcing the banks to choose between operating as either a commercial or an investment bank. Legislation to enforce complete separation was rejected because it was concluded that there are some significant benefits from allowing banks to diversify their activities. However, the 2013 Banking Reform Act gave the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA – see below) the power to enforce full separation on individual banks if deemed necessary.

c) Credit creation

Students should understand that banks create credit by giving loans to their customers. Providing a loan, which is an asset to the bank, creates a corresponding liability for the bank in the form of a deposit in the customer’s account. A bank deposit is an asset for the bank’s customer and deposits can be transferred between customers using, for example, cheques, debit cards and standing orders. Bank deposits are both a store of value and a medium of exchange; they are the largest component of the money supply.

Candidates should understand that there are limits on a bank’s ability to create credit and these include: their holdings of capital and liquid assets, the demand for credit and the policy of the central bank. A central bank, such as the Bank of England, can affect the demand for credit by, for example, changing Bank Rate and it can also affect bank lending by changing required capital ratios (ie the amount of capital on a bank’s balance sheet as a proportion of its loans) and by altering the value of liquid assets the banks must keep. At present, the Bank of England does not attempt to control bank lending by fixing or changing reserve ratios such as the cash ratio or any other liquid assets ratio. However in the United States, the Federal Reserve does specify reserve requirements (liquidity ratios) with which the banks have to comply. In 2019, the ‘liquidity coverage ratio’, introduced as part of the Basle III agreement, will have to be implemented in the UK.

Whilst students should understand how capital and reserve ratios (liquidity ratios) affect a banks’ ability to create credit, they will not be required to calculate the ‘credit multiplier’. However, they should appreciate why, other things being equal, higher capital and reserve ratios (liquidity ratios) mean that banks’ ability to create credit is likely to be reduced. A simple numerical example may help to illustrate the principle. If a bank’s capital equals £3bn and it is required to maintain a capital to loans ratio of at least 10%, then the maximum value of the loans it can provide is £30bn. However, raising capital ratios may encourage banks to issue more shares, reduce dividends or limit bonuses rather than restrict lending. Other things being equal, if a bank acquires more capital or the capital ratio is reduced, the bank will be able to increase the value of loans it has on its books.

d) Other institutions operating in financial markets

Students are expected to be aware that there are other types of financial institution that operate in UK and global financial markets. However, they are not required to know their activities or functions. Such institutions include: insurance companies, pension funds, hedge funds and private equity companies. They should also be aware that the shadow banking sector supplies an increasing amount of credit to borrowers.

The shadow banking system includes financial intermediaries involved in the provision of credit across the global financial system, but who are not subject to regulatory oversight. The shadow banking system also includes the unregulated activities of regulated financial institutions. The volume of business carried out in the shadow banking system has grown substantially over the past 20 years and this is of concern to the authorities since the unregulated shadow banking system adds to systemic risk.

Teachers and students who are interested in the institutions in the shadow banking system and the assets traded, eg money market funds and securities (such as mortgage-backed securities), should easily be able to find relevant information on the Internet. The AQA specification does not require that students know about the activities of participants in the shadow banking system but they should be aware that such unregulated financial markets exist and that they increase the risk of financial crises developing.

Central banks and monetary policy

a) The main functions of a central bank

Students should understand that a central bank has two key functions, ie to maintain financial stability and to help the government in maintaining macroeconomic stability. The provision of liquidity insurance, by acting as the lender of last resort, is crucial to the maintenance of financial security. However, achieving financial stability is also supported by other activities that a central bank undertakes, including monitoring and regulating financial institutions. Central banks use monetary policy to try to maintain macroeconomic stability but the achievement of macroeconomic stability is unlikely to be realised unless there is also financial stability. Recurrent crises in financial markets are likely to severely disrupt the real economy

As far as macroeconomic stability is concerned, students should know that the remit of the Bank of England is to deliver price stability, ie low inflation, and, subject to that, to support the government’s economic objectives including those for growth and employment. Price stability is defined by the government’s inflation target, currently 2% CPI. The remit emphasises the importance of price stability in achieving macroeconomic stability, and in providing the right conditions for sustainable growth in output and employment. Macroeconomic stability is, of course, also affected by the fiscal and supply-side policies

Students should also appreciate that the central bank carries out other related functions such as: controlling the note issue, acting as the bankers’ bank, acting as the government’s bank, buying and selling currencies to influence the exchange rate, and liaising with overseas central banks and international organisations. The Bank’s role as banker to the government has been significantly reduced; since May 1998 the Debt Management Office (DMO) has issued gilts on behalf of the Treasury and in 2000, the DMO took over responsibility for issuing Treasury bills and managing the government’s short-term cash needs

b) Monetary policy

The aims and operation of monetary policy have always been an important part of A-level Economics specifications and are included in the standard A-level text books. This Teacher Guide does not aim to repeat what is covered thoroughly elsewhere. However, monetary policy has evolved since the previous specification and many of the A level textbooks were written. Many of the changes have been prompted by the financial crisis and the reliance that has placed on monetary policy to get the economy growing again.

The specification states that ‘Students should understand recent instruments of monetary policy such as: quantitative easing, Funding for Lending and forward guidance’. It is inevitable that monetary policy will continue to involve and it is important that teachers and students keep up to date with any significant developments. Adjustments in Bank Rate, designed to influence short-term interest rates, will remain the most important instrument of monetary policy but students should understand the reasons for the introduction of so-called unconventional monetary policy measures such as the Asset Purchase Scheme, ie quantitative easing. They should also understand how QE and other monetary measures are likely to affect the real economy. The Bank of England provides a variety of resources, many of which are listed at the end of this Teacher Guide, that explain the channels through which such measures are expected to influence the economy.

c) How the Bank of England affects the money supply

It should be understood that the Bank does not target the rate of growth of the money supply. However, the growth of money and credit can provide an important indicator of the current and future path of the economy. If the stock of money is growing too rapidly or the amount of credit is expanding too fast, this may indicate that inflation is likely to accelerate and/or that a potentially dangerous rise in asset prices, a speculative bubble, is on the horizon. A contraction in the stock of money and a reduction in the ability of economic agents to access credit can drive an economy into recession, possibly resulting in deflation.

Policies adopted by the Bank can affect the rate of growth of both narrow and broad money and the supply of credit. Changes in interest rates will affect people’s willingness to borrow, this will affect bank lending and hence the stock of money. QE tends to reduce long-term interest rates and increases the commercial banks’ holdings of balances at the Bank of England, affecting the banks’ ability to create credit. The Funding for Lending Scheme provides an incentive for the banks to lend more to business by reducing the banks’ cost of borrowing, allowing them to lend more cheaply to firms. If banks are required to increase their capital or liquidity ratios, other things being equal, this is likely to reduce bank lending and thus the growth of the money supply.

The regulation of the financial system

As stated above, providing liquidity insurance is a crucial element in helping a central bank to achieve its objective of financial stability. This was recognised by the eminent Victorian writer and journalist Walter Bagehot.

Walter Bagehot’s dictum has been quoted as, ‘To avert panic, central banks should lend early and freely (without limit), to solvent firms, against good collateral, and at high rates’.

In the context of the UK economy, when the Bank of England acts as lender of last resort, its lending to the banks is usually secured against high quality assets and they are charged a minimum of Bank Rate in market-wide operations, and a premium over Bank Rate for support to individual institutions. This means that the banks will only want to access emergency lending from the Bank of England if they can’t obtain the funds they need from elsewhere, eg by borrowing on the interbank market. A penal rate of interest, above Bank Rate, is charged for liquidity provided to a distressed bank.

It should be appreciated the lender-of-last-resort function can be divided into:

- the routine provision of liquidity from the central bank that is on-going throughout the year and designed to offset the regular ebb and flow of money in and out of the banking system

- the emergency provision of liquidity to a bank that has cash flow problems

- the emergency provision of liquidity to financial markets when there is a systemic problem such as during the 2008 – 09 credit crunch.

The Bank of England also helps to regulate financial markets and this is another key part of its approach to maintaining financial security.

a) Regulation of the financial system in the UK

In 1986, Margaret Thatcher’s government began the process of deregulating financial markets by introducing a policy that is known as ‘Big Bang’. London was becoming uncompetitive and losing business to other financial centres. The policy was introduced to arrest the decline in London as a financial centre and was successful in revitalising financial institutions and markets located in the capital. The policy of deregulation was augmented by the Labour government that was elected in 1997. However, the policy of ‘light touch regulation of financial markets’, that was adopted by most countries around the world, has been blamed for the recent financial crisis. This has led to a reversal of policy with, for example, the passing of the Dodd-Frank Act (2010) in the USA and the Financial Services Act (2012) in the UK

The Financial Services Act strengthened the role of the Bank of England in regulating the financial system. It established the Financial Policy Committee (FPC) and the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), both of which are part of the Bank of England. It also set up the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) which works in conjunction with the FPC and PRA but the FCA is not part of the Bank. Students should understand the role of each of these institutions in achieving financial stability, as outlined below.

The FPC is primarily responsible for macroprudential regulation whereas the PRA and FCA are mainly responsible for microprudential regulation.

Macroprudential regulation is concerned with identifying, monitoring and acting to remove risks that affect the stability of the financial system as a whole.

Microprudential regulation focuses on ensuring the stability of individual banks and other financial institutions; it involves identifying, monitoring and managing risks that relate to individual firms.

The Financial Policy Committee (FPC)

The independent FPC was formally established on 1 April 2013, although an interim FPC first met in 2011. The primary objective of the committee is to identify, monitor and take action to remove or mitigate systemic risks to the UK financial system. Its secondary objective is to support the economic policy of the government. Systemic risks are those which could trigger the collapse of the whole, or a significant part, of the financial system. When the financial crisis hit the world economy, it was judged that if some banks collapsed it would generate a run on other banks; the problems would spread with devastating consequences. Such banks were judged to be ‘too big to fail’. It is the role of the FPC to identify such risks and to take action to make the system more resilient to shocks. The FPC has two main powers: it can issue mandatory directions to the PRA and the FCA, and it can make recommendations to anyone, including the government. It has the power to make comply-or-explain recommendations to the PRA and FCA.

The Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA)

The PRA is responsible for the supervision of banks, building societies, credit unions, insurers and major investment firms. It sets standards and supervises financial institutions at the level of the individual firm. The PRA regulates by setting standards which financial institutions are required to follow and supervises by assessing the risks posed by individual financial firms and taking action to make sure they are managed properly. It aims to promote the soundness of banks and other firms providing financial services so that the stability of the UK financial system is enhanced. The PRA may require individual institutions to maintain specified capital and liquidity ratios. However, the PRA does not seek to operate a ‘zero-failure’ regime. Instead, the PRA tries to ensure that if a financial firm fails it does so in a way that avoids significant disruption to essential financial services.

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA)

The aim of the FCA is to protect consumers, to promote competition between the providers of financial services and to maintain a stable, resilient financial services industry. The FCA uses its rule-making, investigative and enforcement powers to protect consumers and to regulate the financial services industry.

b) Bank failures, liquidity assurance and moral hazard

The regulation of the banks includes the establishment of minimum liquidity and capital ratios. At an international level, these requirements are based on the recommendations of the Basel Committee. In Europe, a directive has been issued (CRD IV) that enshrines the latest Basle III recommendations into law.

If banks do not have sufficient capital, they are at risk from a fall in the value of their assets. Insufficient liquidity makes them vulnerable to a run on the bank which can cause a bank to fail, even if its assets are greater than its liabilities. The willingness of the central bank to act as lender of last resort and provide liquidity insurance increases confidence in the stability of the banks. It is necessary because the banks borrow short term but lend long term.

However, central bank support for financial institutions and government bailouts can result in banks taking too many risks because they believe that the authorities will not allow them to fail. Moral hazard exists when one economic agent decides how much risk to take in the knowledge that if things go wrong, someone else will bear a significant portion of the cost. Investing in high risk assets can lead to high profits and unless there is the possibility that financial institutions will be allowed to fail, there is insufficient incentive to act prudently. Regulations imposed on the banks are designed to limit their ability to act recklessly and other measures, such as imposing a firewall between the commercial and investment activities of the banks, should mean that the more risky parts of the banks can be allowed to fail without impairing the indispensable provision of vital financial services.

c) Systemic risk, financial instability and the real economy

Students should recognise that this topic links very closely with a number of other parts of the specification. For example, when responding to a question on the causes of cyclical instability, they might be expected to analyse the impact of financial instability on growth, employment and price stability. However, they should appreciate that financial instability is not the only cause of cyclical instability. Nevertheless there is a lot of evidence to suggest that a recovery from a financial crisis usually takes much longer than from a recession that is not accompanied by major problems in financial markets.

Students should appreciate that financial crises often occur after a prolonged period of prosperity. Low interest rates, easy credit and rising asset prices are accompanied by high levels of debt and overconfidence. A crisis can be fuelled by destabilising speculation whereby people buy assets in the anticipation of future capital gains that are not justified by the ‘real worth’ of the assets. Financial institutions may support such speculation by reckless lending. Herding behaviour can lead to asset price bubbles followed by a collapse in asset prices.

A fall in asset prices contributes to a generalised recession in a number of ways. If the value of the assets held by a financial institution falls, the loss in value of these assets leads to an equivalent reduction in the capital base of the institution. In the good times, excessive and risky lending by banks meant that when the economy slows down some loans will not be repaid and some other assets held by the banks, eg mortgage-backed securities, will fall in value. This erosion in their capital base, resulting from the fall in the value of their assets, is also likely to be accompanied by liquidity problems. As a result, they are forced to restrict their lending and interest rates will rise, ie there is a credit crunch. Restricted bank lending will lead to lower aggregate demand as investment and household consumption falls. The fall in asset prices also affects confidence and reduces household wealth, intensifying the fall in aggregate demand. If households have large debts, built up during the time of prosperity, when the economy starts to contract, households are likely to try to reduce their indebtedness. They attempt to save more and pay off debts rather than take out additional loans. In this context, some teachers might wish to introduce their students to the ideas of Hyman Minsky. A web link to an Analysis programme broadcast by BBC Radio 4 is included in the resources section of this document.

The likelihood that financial instability will result in economic instability is a fundamental reason why governments around the world have tightened the regulations with which financial institutions have to comply. It should be recognised that what might initially appear to be relatively minor problem in one part of the global financial market can very easily spread and lead to a much more serious situation. It is generally, but not universally, agreed that financial institutions should be subject to a much stricter regulatory regime than existed in the lead up to the 2007-08 financial crisis. The inherent risks in the financial sector and the importance of financial institutions for the efficient functioning of an economy mean that problems affecting financial markets can be very damaging. If banks have to be bailed out by the government, the cost to the taxpayer is very high. Central banks provide liquidity insurance to the banking sector and the acceptance of regulation can be regarded as way of moderating the moral hazard that results.

However, students should understand that regulation is not without its problems; there is always the danger of regulatory capture, it might stifle innovation, restrict the supply of credit to economic agents who could make good use of additional funding and lead to rapid growth in an unregulated shadow banking sector

The specification states that ‘teachers should provide students with the opportunity to explore the disagreements that exist between economists and current economic controversies’. Students might wish to consider the free-market view that state intervention has more costs than benefits compared to a world in which markets operate without any intervention. In this context, they could be introduced the ideas of economists of the Austrian school such as Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig Von Mises. Austrian economists believe that it is intervention in financial markets, including the central bank action to manipulate interest rates, which causes financial crises. Such economists believe that markets should be allowed to allocate financial resources and that any form of intervention is likely to be harmful. According to this view, the reason why problems arise is not because markets don’t work but because state intervention does not allow markets to work properly.

Resources

Most of the existing A-level textbooks provide some useful coverage of this area but are generally out of date. However, Hodder published a 2nd Edition of Ray Powell’s AS and A2 Economics textbook in 2014, and the following are both useful:

AQA AS Economics (2nd Ed), R Powell, Chapter 23

AQA A2 Economics (2nd Ed), R Powell, Chapter 18

The new textbooks that are due to be published in 2015 to accompany the AQA Economics specification will include up-to-date sections on ‘Financial markets and monetary policy’. There is also a wide range of other resources available on the internet, and the Bank of England website is a particularly useful source.

Accessible books

Two books written by Philip Coggan, who is currently the Buttonwood columnist for The Economist, will be accessible to most A-level students. They are published by Penguin as paperbacks and Kindle versions are available to download.

- Paper Promises – Money, Debt and the New World

- The Money Machine – How the City Works

Two books that provide a more formal and detailed coverage of the area are:

- An Introduction to Global Financial Markets by Stephen Valdez and Philip Molyneux

- The FT Guide to Financial Markets by Glen Arnold

Some students and teachers might want to dip into these two books to develop and extend their knowledge of financial markets but, whilst they are not overly complex, they go well beyond what is required by the AQA specification.

Pamphlets and articles

Bank of England

- Your money and the financial system: This is an invaluable little booklet that provides an excellent summary of many of the topics. Hard copies can be obtained by emailing the bank.

- Postcards from the Bank of England: These postcards provide brief overview of some aspects of the Bank’s work and the role of financial markets. Hard copies can be obtained by emailing the bank.

- Bank of England market operations guide: This online guide explains in more detail how and why the Bank of England operate in markets, and how their operations work in practice.

- Quarterly Bulletin: This document is too detailed for the majority of A-level students although some may find that reading parts of it is worthwhile. Some teachers will also find it very useful.

- How monetary policy works: This provides a useful overview of monetary policy.

- Liquidity insurance: This provides an explanation of ways in which the Bank fulfils its role as lender of last resort. There is further detail in the ‘red book’ mentioned earlier. However, it should be noted that students are not expected to know the different ways in which the Bank provides liquidity, eg they do not need to know the difference between the Discount Window Facility and the Contingent Term Repo Facility.

- There are a number of other useful pages that are easily accessible from the home page of the Bank of England website.

Videos

Bank of England

The Bank of England has its own YouTube channel. This is regularly updated and will include, for example, the latest quarterly inflation report webcast. Examples of other video clips that teachers will find particularly useful are:

- Money in the modern economy – an introduction

- Money creation in a modern economy

- Quantitative easing – how it works

Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve also has its own YouTube channel.

The previous chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank, Ben Bernanke, gave a series of four lectures to students at Washington State University. The first 20 minutes of the first lecture focuses on the key functions of a central bank and provides an excellent introduction to the topic for A-level students. The lecture series lasts about 5 hours and there is unlikely to be enough time to show all four programmes. However, as with some of the other resources listed above, many teachers and some students will enjoy listening to the lectures. They cover:

- the history of central banking

- a brief history of the great depression and the post WW2 economy

- the great moderation

- the lead up to the financial crisis

- the response of the US authorities to the financial crisis.

Links to each of these talks is given below:

- Lecture 1 The Federal Reserve and the Financial Crisis Part 1

- Lecture 2 The Federal Reserve and the Financial Crisis Part 2

- Lecture 3 The Federal Reserve and the Financial Crisis Part 3

- Lecture 4 The Federal Reserve and the Financial Crisis Part 4

If you search YouTube, you will of course find many other clips that can be used in the classroom.

BBC Radio Podcasts

Analysis on BBC Radio 4 has produced a number of programmes on economics related topics.

One programme that may be of particular interest is ‘Why Minsky matters’. Since the financial crisis the ideas of Hyman Minsky have become very influential, and this programme provides a summary of his key ideas.

Other web links

This New Economics Foundation blog on money creation provides a commentary on how banks create credit and has a link to a book entitled Where does money come from, first published in 2011.

Useful statistics

Some teachers might want to provide up-to-date statistics for their students or set research tasks for homework. The following are examples of useful sources of macroeconomic and financial data:

- The Bank of England online database, where data on M0, interest rates, exchange rates and much else can be downloaded.

- ONS data on the economy

For international data, the OECD and IMF have good and comprehensive online databases.

There are also useful introductions to the ideas of Austrian economists and Hyman Minsky, providing two different perspectives on financial markets and their significance for the macroeconomy.