The EBacc reconsidered

By Emma Armitage

Published 30 Oct 2015

The English Baccalaureate (EBacc) was introduced in 2010 by Michael Gove, the then Secretary of State for Education. It is a school performance measure that indicates the number of students who achieve A* to C grades in a specific suite of GCSE subjects. These currently comprise English, Maths, Science (including Computer Science), a humanity (Geography or History), and a language. The government’s rationale was that these subjects represent a rigorous academic core, which more pupils should study in order to ‘keep their options open’ for post-16 progression. Fast-forward five years and the EBacc is the focus of an upcoming autumn consultation.

EBacc for all

The EBacc has ignited widespread debate across the education sector. One of the most hotly contested issues has been whether a core curriculum is suitable for everyone. The EBacc is intended to reduce educational inequality by providing all pupils with the opportunity to study the subjects that best prepare them for a successful future. This idea receives some support from Michael Young, who argues that all students are entitled to the ‘powerful knowledge’ that can potentially be derived from the EBacc subjects (Knowledge and the future school: Curriculum and social justice, 2014).

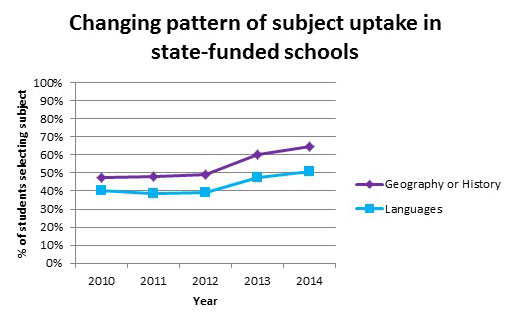

Furthermore, research has shown that students who take the EBacc subjects at GCSE are less likely to be categorised as ‘not in education, employment or training’ at the age of 19. In light of this, statistics that show a rise in the uptake of non-compulsory (humanities and languages) EBacc subjects since 2010 are positive.

However, future success depends on achievement in the subjects studied, and not everyone is convinced that this will be comparable for advantaged and disadvantaged pupils. While many school leaders recognise the merits of a core curriculum, some remain concerned that the academic rigour of the EBacc subjects is unsuitable for lower-performing students, who are disproportionally represented in the disadvantaged category. For these students, the path to success might reside in the study of other subjects or vocational qualifications.

Similarly, there are concerns that the EBacc could draw schools’ attention away from disadvantaged pupils by intensifying the focus on C/D borderline pupils who are most likely to attain the EBacc. Nonetheless, it was recently announced that all pupils who started secondary school in September 2015 will be expected to take the EBacc subjects at GCSE in 2020. Since it will be several years before the outcome of this insistence on ‘EBacc for all’ is known, it remains to be seen whether it can successfully level the educational playing field for disadvantaged pupils as is intended.

A perfect partnership? EBacc and Ofsted

There is ongoing concern regarding future use of the EBacc.

Initially, the EBacc’s primary function was to provide parents with additional information to guide school choice, however recently it has been suggested that schools in which all pupils do not study the EBacc will be ineligible to receive the highest Ofsted ratings. There is, of course, something to be said for providing students with clear parameters on subject choice – their interests at the age of 14 might drive unsuitable choices, which will narrow their options further down the line.

However, the suggestion that Ofsted ratings will be used as an incentive for implementing this guidance has led some school leaders to pre-emptively state that they will not prioritise the EBacc for the sake of their Ofsted rating. The Head of Ofsted, Sir Michael Wilshaw, has yet to make a definitive statement on the proposal but recent comments suggest that he has reservations about how appropriate it is for all young people to study a heavily academic curriculum.

Looking forward to the autumn consultation, then, it is clear that two questions dominate the minds of education professionals: will all pupils have to study the EBacc subjects at GCSE, and if it is formalised, what will the relationship between EBacc and Ofsted inspections look like? The answers to these questions could have a significant impact on the UK’s educational landscape, and will certainly provide researchers with opportunities for assessing the interaction between policy and assessment, and the subsequent impact on pupils.

Emma Armitage

Keywords

Related content

About our blog

Discover more about the work our researchers are doing to help improve and develop our assessments, expertise and resources.

Share this page

Connect with us

Email: research@aqa.org.uk

Work with us to advance education and enable students and teachers to reach their potential.